On 26th July 2025, a lot of Ghanaians and music lovers were struck with the unfortunate demise of Ghana’s iconic, legendary highlife musician Charles Kwadwo Fosu, a.k.a Daddy Lumba. The family announced the death of the highlife legend, and the necessary arrangements as custom demands to receive well-wishers and the opening of a Book of Condolence at his residence. Thereafter, a one-week observation event was organised at Independence Square on 30th August 2025 to celebrate the life and legacy of the legend. During this period, all seemed to be quite peaceful at the camp of the late Daddy Lumba’s Family, at least as far as the public knows. There were, however, rumours that the two women he was involved with, namely Akosua Serwah Fosu and Priscilla Ofori a.k.a Odo Broni, were at loggerheads as to who was the surviving spouse of the late Daddy Lumba.

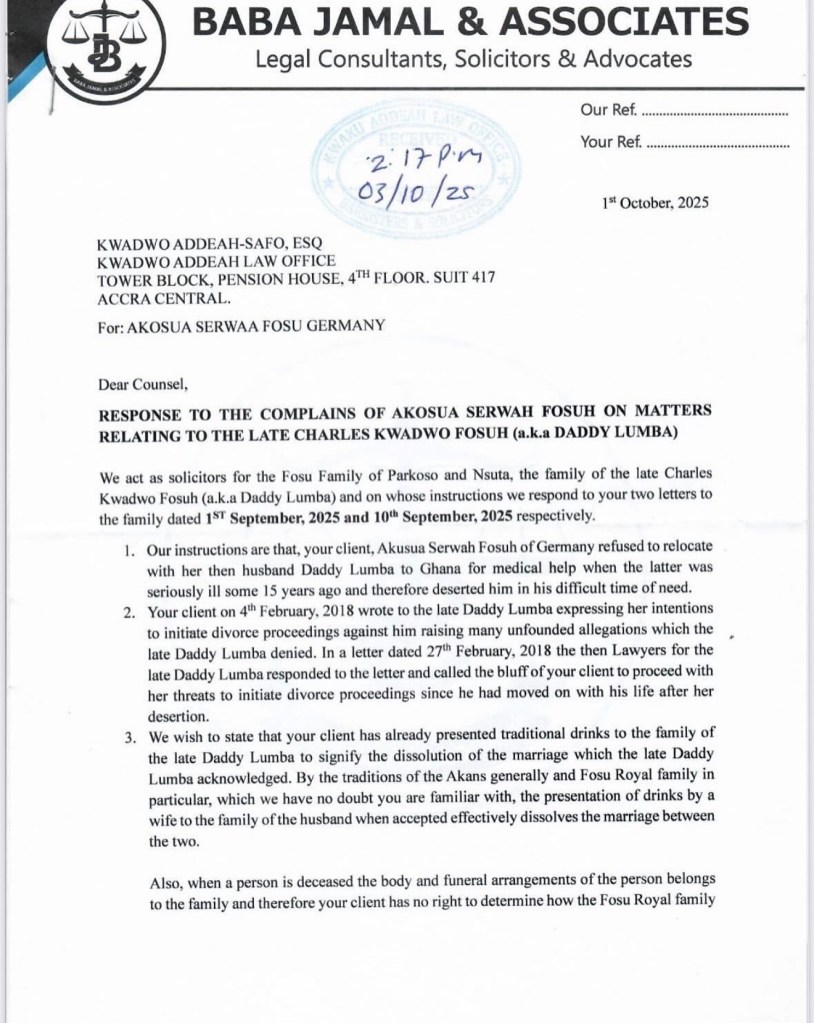

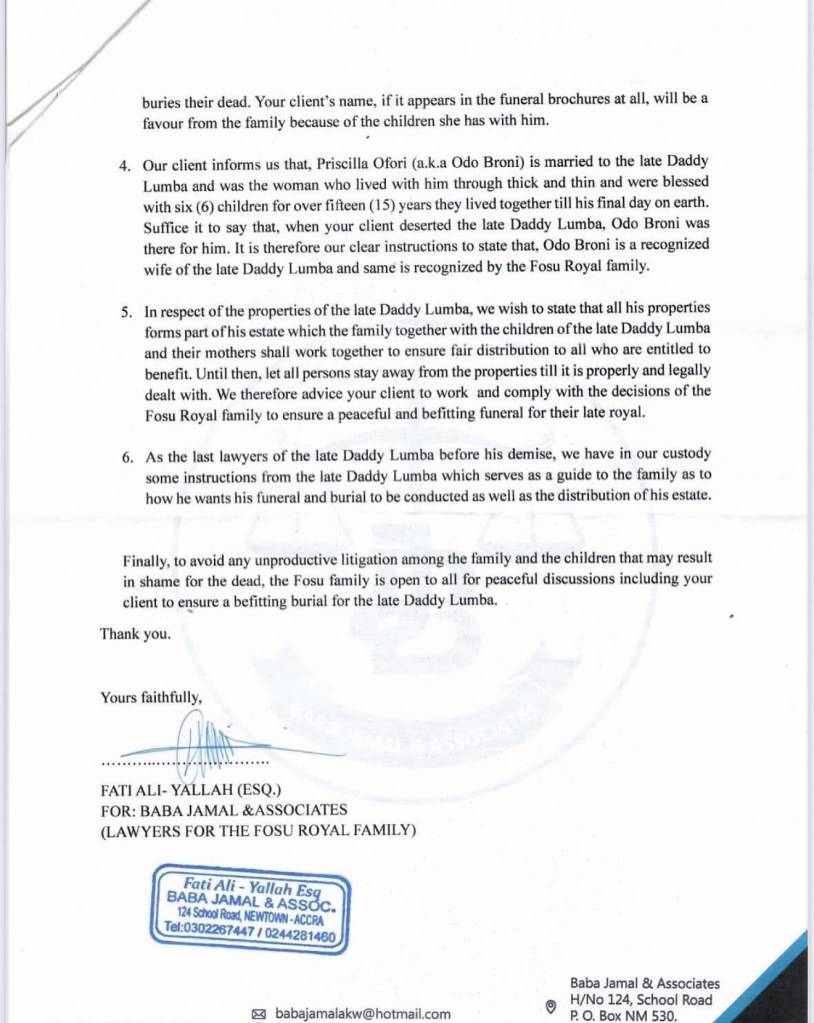

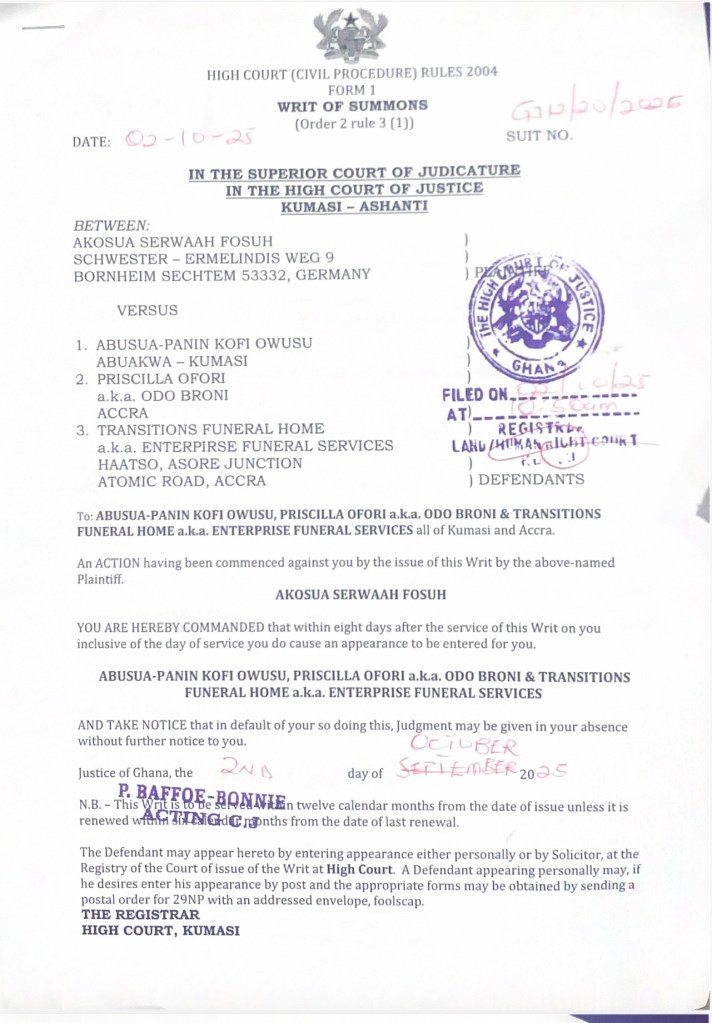

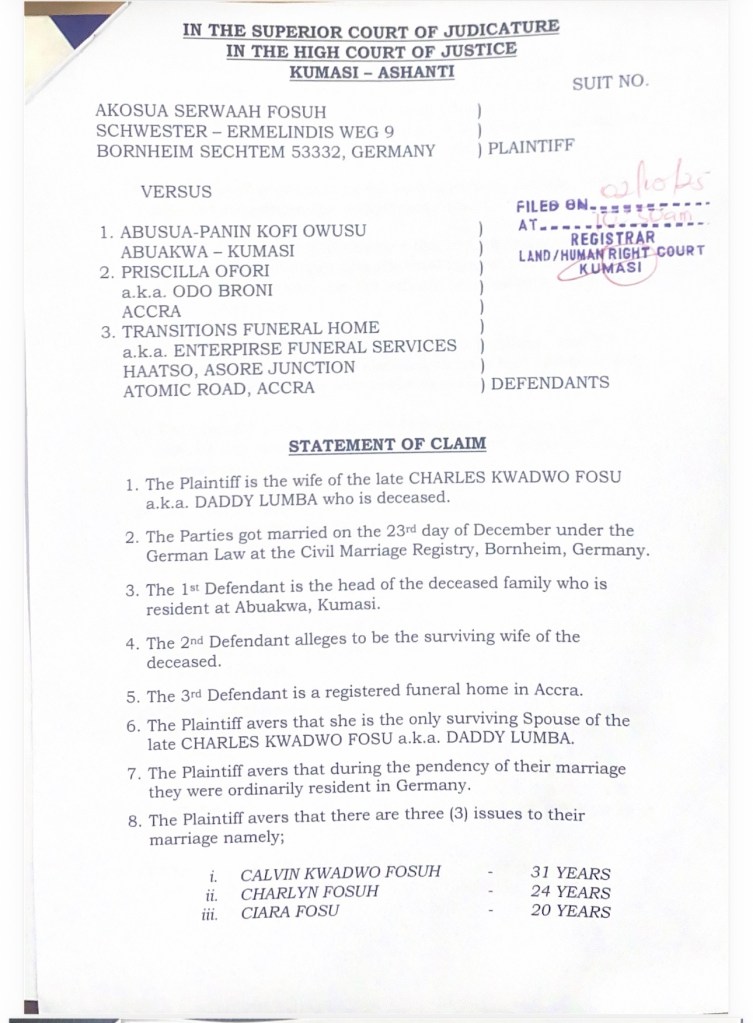

Things began to go awry after the family announced the final funeral rites would be held on Saturday, December 6, 2025, at Baba Yara Sports Stadium, Kumasi. Shortly after this announcement, a lawsuit surfaced online filed by Akosua Serwah Fosuh (Suit No. GJ/12/2025 – Akosua Serwah Fosu vrs Abusuapanin Kofi Owusu & 2 Ors), claiming to be the sole surviving spouse seeking reliefs, among other things, including a declaration that she is the only surviving spouse of the late Daddy Lumba, a declaration that only she has the right to perform the widowhood rites, and an order restraining Odo Broni from portraying herself as the surviving spouse of the late Daddy Lumba. The case filed by Akosua Serwah Fosuh was accompanied by an application for an interlocutory injunction aiming to halt the performance of the burial and final funeral rites of the late Daddy Lumba. Additionally, a letter also emerged online from the lawyers representing the Fosu Family (Daddy Lumba’s Family), responding to complaints made by Akosua Serwah Fosu regarding matters related to the late Daddy Lumba.

Since these issues came to the limelight, many people have expressed diverse opinions about who is right and who is wrong. However, amid all these discussions, the questions on the minds of many Ghanaians are what the law says about these developments, what the possible outcomes of the case are, and what lessons can be learned. At the centre of this issue are the principles of family law, customary law, succession, and conflict of laws. This piece aims to analyse the known facts in light of the existing law.

Validity of the late Daddy Lumba’s Marriage to Akosua Serwah Fosuh

It is undisputed that the late Daddy Lumba’s marriage to Akosua Serwah Fosuh was first in time to that of Odo Broni. It can also be assumed that the said marriage was initially celebrated under Ghanaian customary law and later under German law. Under Ghanaian law, it is well established that customary marriage can be potentially polygamous, meaning a husband may take on an unlimited number of wives as long as he remains married under customary law (See case of Graham v Graham [1965] GLR 407). However, customary marriage can be converted into an ordinance (marriages under Part III of the Marriages Act, 1985 (CAP 1279) or civil marriage, which is monogamous, meaning the husband is restricted to only one wife.

Once a marriage is converted, it extinguishes the rights and privileges associated with customary marriages (See the case of Coleman v Shang (1959) GLR 390). This means that the ordinance marriage now solely determines the rights and privileges of the married parties. Therefore, a person who has converted his customary marriage to an ordinance/civil marriage cannot legally marry another wife under customary law. Additionally, such a person cannot divorce his or her spouse using the customary law procedure for dissolution of marriage. These legal principles, affirmed in the longstanding case of Coleman v Shang (supra), remain valid and applicable to date.

Daddy Lumba’s marriage to Akosua Serwah Fosuh was converted from customary marriage to an ordinance/civil marriage on 23rd December 2004 at the Civil Marriage Registry in Bernheim, Germany, under German law. Therefore, the rights and privileges of the two parties to the marriage are governed by the laws regulating civil marriages. One might ask, since the marriage was celebrated in Germany, is it enforceable in Ghana? Yes. Under Ghanaian conflict of law rules, marriages celebrated in foreign countries are recognized under Ghanaian law as long as they meet all the criteria of a valid marriage under the laws of the country where the marriage was contracted. Hence, the civil marriage between Daddy Lumba and Akosua Serwah Fosuh is recognised under Ghanaian law unless otherwise proven that the marriage was not valid according to the “lex loci contractus/celebrationis” (the law of the place where the marriage was celebrated/contracted), which is German law.

Divorce and Dissolution of the late Daddy Lumba’s marriage to Akosua Serwah Fosuh

In the letter from the lawyer for the family of Daddy Lumba, written to Akosua Serwah through her lawyer, it is stated in paragraph 3 that “ We wish to state that your client has already presented traditional drinks to the family of the late Daddy Lumba to signify the dissolution of the marriage, which the late Daddy Lumba acknowledged. By the traditions of the Akans generally and Fosu Royal family in particular, which we have no doubt you are familiar with, the presentation of drinks by a wife to the family of the husband when accepted effectively dissolves the marriage between the two”. Based on the foregoing, the Family claims the civil marriage between Daddy Lumba and Akosua Serwah was dissolved. This essentially means that Daddy Lumba was free to marry Odo Broni, who is now claiming to be the surviving spouse. This position, however, does not conform to the current jurisprudence on matrimonial causes in Ghana.

In Ghana, a customary marriage can be dissolved under customary law by performing the necessary ceremonial rites, such as one spouse returning the drinks (“ti nsa”) as is usually done in Akan tradition, and if accepted by the family of the other spouse, the marriage is deemed dissolved. However, a customary marriage which has subsequently been converted into an ordinance/civil marriage cannot be dissolved using the customary law procedure explained above. As already mentioned, once a customary marriage is converted to an ordinance/civil marriage, it extinguishes all rights and privileges associated with the customary marriage. The case of Coleman v Shang (supra) confirms the position of the law in this regard as follows:

“(3) that a person subject to customary law, who marries under the Marriage Ordinance, remains subject to customary law in all matters save those specifically excluded by the statute and any other matters which are necessary consequences of the marriage under the Ordinance. Thus …(ii) a man married under the Ordinance cannot claim the benefit of the provisions of customary law for divorcing his wife.”

The incidents of Daddy Lumba’s civil marriage with Akosua Serwah will be treated in accordance with German law under which it was contracted. Thus, to determine whether the said civil marriage was properly dissolved, it must be looked at in the light of German law. Section 36 of the Matrimonial Causes Act, 1971 (Act 361) provides that the court in Ghana will recognize a foreign decree of divorce or dissolution of marriage obtained by judicial process that has been granted by a tribunal which had a significant and substantial connection with the parties to the marriage and is in accordance with the law of the place where both parties to the marriage were ordinarily resident at the time of the action dissolving or annulling the marriage. Thus, if a divorce is properly granted in a German court/tribunal, it is recognizable and enforceable in Ghana.

I will not attempt to provide an exposition on German law as it pertains to civil marriages and their dissolution in this piece, as section 40 of the Evidence Act, 1975 (NRCD 323) states that the law of a foreign country is presumed to be the same as the law of Ghana. Therefore, once Akosua Serwah has initiated this case in Ghana, the court may presume that German law concerning the incidents of German civil marriage is equivalent to that of an ordinance marriage under the Marriages Act. An ordinance/civil marriage can only be dissolved by the death of one of the parties or through the institution of divorce proceedings leading to a court decree dissolving the marriage. Anything less than this will not be recognized as a proper dissolution.

The letter from the Fosu Family refers to Akosua Serwah’s alleged desertion as a validation for the purported dissolution of her marriage to the late Daddy Lumba. Desertion can only be a ground on which a court may dissolve a marriage, but desertion in itself does not dissolve a marriage (See sections 2(c) & 5 of the Matrimonial Causes Act). Thus, desertion of a spouse, no matter how long it takes, cannot metamorphose into a dissolution of a marriage to give the other spouse the right to contract a new marriage.

The late Daddy Lumba contracted a civil marriage with Akosua Serwah in Germany, and so far, as there have not been any previous divorce proceedings in a court of competent jurisdiction dissolving the marriage either in Germany or Ghana, then the parties were deemed still married until his demise. It is only death or a certificate of divorce issued by a court of competent jurisdiction that could have properly dissolved the marriage of the late Daddy Lumba to Akosua Serwah, not desertion coupled with the return and acceptance of customary drinks.

Validity of the late Daddy Lumba’s marriage to Odo Broni

Since the late Daddy Lumba’s marriage to Akosua Serwah had not been legally dissolved as explained above, he could not have entered into another marriage, whether customary or under ordinance, with another woman. Section 76 of the Marriages Act provides that a person who is married under ordinance shall not, during the continuance of that marriage, contract a valid marriage under an applicable customary law. Therefore, it does not matter how many years Daddy Lumba had been with Odo Broni or how many children he fathered with her; once his previous civil marriage was still in effect at the time of his customary marriage to Odo Broni, that marriage is a nullity from the outset.

From the above analysis of the known facts and the applicable laws, it is clear that Akosua Serwah Fosuh is the sole surviving spouse of the late Daddy Lumba.

Court Case, Burial and Final Funeral Rites of the late Daddy Lumba

The case commenced by Akosua Serwah seeks to do two things. First is for the Court to confirm her status as the sole surviving spouse, and second is to confer all the rights and benefits of being a sole surviving spouse. As part of the rights, Akosua Serwah is seeking to get the Court to enforce her “right” to be consulted and participate in the final funeral rites of the late Daddy Lumba and to perform the accompanied widowhood rites. At the heart of this case will be the issue of whether the performance of the widowhood rite is a legally recognizable and enforceable right of a surviving spouse, which is justiciable.

Interest of Akosua Serwah Fosuh in Daddy Lumba’s Final Funeral Rites

Under Ghanaian law, it is well settled that the corpse does not form part of the estate of the deceased; it belongs to the customary family of the deceased, and it is this family that decides on matters of burial and funeral. This has been affirmed in the case of Neequaye & Anor vrs Okoe (1993-94) 1 GLR 538 and Nii Kpakpo Amaate II v. Daniel Sackey Quarcoopome & 3 Others (2018) JELR 63735.

The mortal remains of Daddy Lumba belong to the Fosu Family, and they have the exclusive right to determine when, how and who will be involved in his burial. The interest of surviving spouses in the burial and funeral rites of their late spouse is summed up by the court in the Neequaye case (supra) as follows “But what I am saying is that at law the wife and children have no inherent right to decide on those issues. Since customary law does what is reasonable, I would think they must be consulted during the arrangements. Indeed, this is the time they need the compassion and sympathetic care of all concerned. Their wishes and views must be heard and considered but I am saying that the state of the law as we have it now, be it statute law or otherwise, does not vest in the spouse and children, particularly in the spouse, the rights sought for by the plaintiffs.”

Ordinarily, Akosua Serwah is considered part of the Fosu Family by virtue of her marriage to the late Daddy Lumba, and as such, her involvement in the funeral is a matter of courtesy extended to her rather than a right as the sole surviving spouse. Although the late Daddy Lumba left behind his last wishes, as noted by the Family’s lawyer, it is well within the rights of the Fosu Family to disregard those wishes. This is because the Fosu Family is obliged to organise a funeral that honours not only the status he achieved in life but also reflects the social standing and dignity of the Family within the community. It must be noted that the widowhood rite, although recognized under Ghanaian customary law, is not a right, privilege or an incident of a marriage, whether customary or ordinance/civil enforceable within our legal framework.

Potential Outcome of Akosua Serwah’s Case

Akosua Serwah may succeed in getting the Court to declare her the sole surviving spouse, therefore entitled to all the rights and privileges of a surviving spouse of the late Daddy Lumba. These rights mainly deal with the administration of the estate of the late Daddy Lumba and not his burial and funeral rites. Thus, the relief sought in the case with regard to the burial and final funeral rites, as well as the application for interlocutory injunction, will most likely fail.

Administration of the Estate of the late Daddy Lumba

Once the late Daddy Lumba is laid to rest, the next issue to be in contention will be the administration of his estate. The administration of the estate of a deceased is governed by two legal regimes, namely testate succession under the Wills Act 1971 (Act 360) and intestate succession under the Intestate Succession Act 1985 (PNDCL 111). There are four issues to be dealt with here. First, which properties form part of the estate of the late Daddy Lumba? Second, which regime of the two legal regimes will govern the administration of his estate? Third, who is entitled to administer the estate of Daddy Lumba and Fourth, who are the beneficiaries of Daddy Lumba’s estate?

If Daddy Lumba left a Testamentary Will behind, then the administration of his estate will be governed heavily by the said Will. The named Executors will be entitled to apply for probate to administer the estate, all other things being equal. The Beneficiaries of the estate will be as stated in the Will. However, assuming Daddy Lumba devised all or most of his properties to Odo Broni and his children, what then becomes the interest of Akosua Serwah in the said properties? In such a situation, the law does not look at whether Odo Broni is a wife or not, but as an ordinary beneficiary of a Will. Once Akosua Serwah get the court to declare her as the sole surviving spouse, then she may consider seeking a remedy under Section 13 of the Wills Act, which allows a surviving spouse or child to apply within three (3) years of the grant of probate for the administration of the estate for reasonable provision for their maintenance on the ground that hardship will be caused to them if the said application is not granted.

If Daddy Lumba did not leave a Will, then the Intestate Succession Act will be applicable in the administration of his estate. The issue as to which properties form part of his estate will have to be dealt with. After which, the issue of who is entitled to apply for letters of Administration to administer the estate arises. Under Order 66 Rule 13 of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2004 (C.I.47), priority of the grant of Letters of Administration is in the following order: any surviving spouse, children, parent and customary successor. Akosua Serwah, as the sole surviving spouse of Daddy Lumba in this case, will be calling the shots when it comes to the administration of his estate, all other things being equal. The estate will, however, have to be distributed in accordance with the Intestate Succession Act using the fractions provided therein. In this scenario, Odo Broni will have no right or interest whatsoever in the distribution of the estate of Daddy Lumba.

There may be a third scenario in which Daddy Lumba left behind a Will; however, the said Will does not cover all the properties that form part of the estate. In case of partial intestacy, section 2 of PNCL 111 provides that a person who dies leaving a Will disposing of part of the estate of that person shall be deemed to have died intestate in respect of that part of the estate which is not disposed of in the Will, and accordingly, PNDCL 111 shall apply to that part of the estate. In such a situation, both legal regimes will apply to the administration of the estate of the late Daddy Lumba, as stated.

Unfortunately, under the current law on marital properties, Akosua Serwah cannot claim any of the properties that form part of the estate of the late Daddy Lumba as marital property, which could have entitled her to the protection of the presumption of ownership of up to a 50% share of the estate. The right of a spouse to claim an equitable share or a 50% share of marital property lapses upon the death of the other spouse unless there is evidence that the parties jointly contributed towards the acquisition of any property, intending that the property belongs to both parties. The basis must not be because the parties are in a position of consanguinity or affinity, but based on the provisions of Article 18 of the 1992 Constitution and Section 40(3) of the Land Act, 2020 (Act 1036). See the case of Louis Anokwafo & 2 Ors vrs Paulina v. Anokwafo (Suit No: PA/0658/2022-judgment dated 17th January 2025). The interest of Akosua Serwah in the estate of Daddy Lumba will therefore be that which accrued under the Wills Act or PNDCL 111, whichever is applicable.

Under both regimes, the Fosu Family has little or no interest in the distribution of the estate of the late Daddy Lumba. If there is a Will, the Family rights or interests are limited to what is stated in the Will. If he died intestate, the Family’s right is limited to the provisions of PNDCL 111.

The rights and interests of the children of both Akosua Serwah and Odo Broni in the estate of Daddy Lumba are protected under both regimes. Thus, the children of Akosua Serwah and Odo Broni will have a reasonable share of the properties. If there is a Will, then the benefit of each child will depend on either what is stated therein, or a reasonable provision made by the court. Where there is no will, all the children will be entitled to an equal share of the portion of the estate allocated to the children as per PNDCL 111.

In summary, the rights and interests of a sole surviving spouse were beautifully put by Lutterot J (as he then was) in the Neeqauye case (supra) as follows: “PNDCL 111 was specifically enacted to give a wife and children the lion’s share of his estate when the husband died intestate. It does not confer on the wife the exclusive right of determining how the corpse is to be handled or dealt with. That the question of who is entitled to inherit and who has responsibility for taking decisions for burial, arranging the funeral of a deceased Ghanaian are two different issues, cannot be over emphasised.” Akosua Serwah, therefore, has a say on matters of inheritance or succession and not the burial and final funeral rites of Daddy Lumba.

Lesson to Learn

This is a complicated matter that can lead to a protracted litigation lasting for years if not handled properly. Thus, all the parties involved may have to iron out their differences and find an amicable resolution of the matter to give our legend a befitting funeral and to ensure a peaceful and smooth administration of his estate.

To those of us still alive and kicking, it is never too early to get our affairs in order. The vital questions you should ask yourself are: are you properly married, are you properly divorced, do you have a Will, and is that Will valid? Sometimes, great men leave behind too many headaches for the beneficiaries of their estate because they fail to organise their affairs properly while alive. You might share your property during your lifetime and retain a lifetime interest, or have your lawyer prepare a Will on your behalf. You can leave behind “last wishes” regarding your burial and final funeral rites, but always remember that once you are gone, your mortal remains become the property of your extended family, not your immediate family.